The modern world has taught us that it is always important to look at the information we consume with a critical eye to seek out the most reliable sources of objective reality. Since the stakes for being inaccurate are often higher at life science and healthcare companies, this task must be taken to the next level. Whether one has a scientific degree or not, we as science communicators often run into occasions when we must learn about a new topic, field, or research method well enough to speak knowledgably and accurately. This can be challenging because we don’t always have expert-level knowledge to call on when filtering the quality of new information. Instead, in those cases, we can draw on our critical comprehension skill set that enables us to rapidly and efficiently make sense of the unknown.

The COVID-19 pandemic has continued to abruptly challenge us with many unknowns. In the research-world, scientists worldwide are trying to publish new work as fast as possible in an effort to stem the tide of the virus. To do so, many are relying on emergency measures to conduct studies and publishing their research, sometimes ahead of peer review or in an accelerated review process to make their results widely available as soon as possible. While accelerated publishing (pre-print or otherwise) enables the global research community to collaborate at a pace to match the pandemic, the rush to publish has placed significant demands on the system that may reduce the typical standards of accuracy and thoroughness found in traditional academic research. No doubt, the pandemic has changed scientific communication.

While scientists may have a better grasp on the appropriate level of confidence to ascribe to new data, a less familiar audience isn’t likely to have the same appreciation of the data collection process, flaws and all. This is especially true when less-versed audiences must rely on news organizations to help translate the information. If the writer misstates or overstates scientific conclusions, their audience may not be equipped to know how seriously to take the information. This is further complicated by the fact that news is being published at a breakneck pace with information that may contradict and convolute the picture. Even still, it is important that each of us, scientists or otherwise, stay engaged and devoted to accurate interpretation of scientific information.

At CG Life, we have to tackle new scientific topics on a weekly, sometimes daily, basis. While we have to get up to speed fast , it is our highest priority to be scientifically accurate in all that we do, especially with pandemic-related topics. To provide some insight into our methodology, this blog post discusses different sources of scientific information out there and the tactics we use to exercise our critical comprehension skills and prioritize scientific information to rapidly become well-informed.

Scientific Information is Shared Through Many Channels

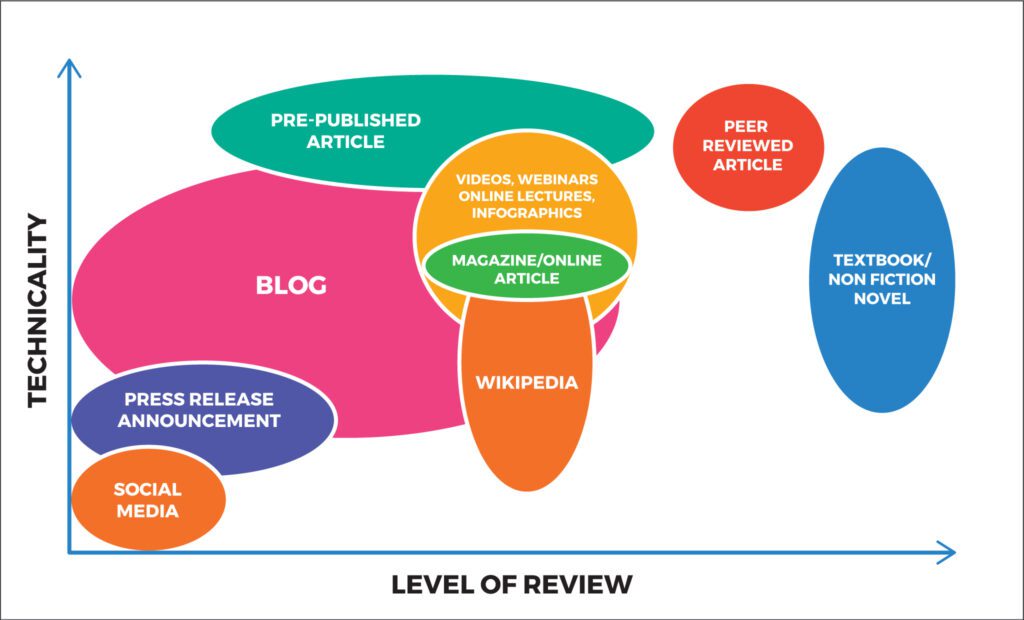

Scientific information is distributed for a variety purposes, explaining its many forms and sources, each geared towards different audiences, knowledge bases, and skillsets. While general sources are written to be accessible to people of all backgrounds, technical sources have more field-specific jargon, data, and references, often intended for those on the cutting edge of research. Furthermore, certain forms of scientific information are held to more rigorous standards and objectivity than others. Altogether, this means that you can find different focuses, levels of detail, and fact-checking depending on what source you’re reading. Below, you can find information on common sources to help readers take appropriate stock of each.

Common Sources of Scientific Information

Peer reviewed article (technical)

- Types of peer-reviewed literature

- Research paper – a paper detailing a scientific question within a field and research done to explore that question: a hypothesis, systematic experiments to test the hypothesis, the results of those experiments, and the conclusions based on those results within the context of the field

- Research communication or letter – brief reports about original research and the resulting data, often used to publish time-sensitive data in a rapidly evolving or competitive field. There is strict, short format, so some experimental details and data may be omitted until a full research manuscript can be written

- Review article – an article written by field leaders that provides a summary of the current understanding and consensus within a scientific field, along with the seminal research that has led to that understanding

- Usually written by one or more scientists responsible for the data

- Extensive peer review process by other experts who only consent to publish when the article meets stringent requirements of accuracy and completeness

- May agree with or challenge established consensus

- Subject to retractions and corrections at any time, providing an additional level of integrity and factualness. For a current database, visit www.retractionwatch.com.

- Impact factor

- Provides a rough assessment of readership and citations for a particular journal, where lower values mean less of both.

- The average journal impact factor in most research fields is between 2-3.

- The top 5% of journals have impact factors ³ 6, and an impact factor of 10+ is excellent

- Note: Scientists are often frustrated by this metric, because high impact factor journals aren’t necessarily better than low impact factor journals: they usually feature the most sensational, groundbreaking research, whereas low impact factor journals may publish details about methodology, more incremental advancement, and sometimes even negative results – so both are important to scientific progress!

Pre-published article (technical)

- Research study published on an online preprint server like arXiv, biorxiv, medRxiv, or ChemRxiv

- Usually written by one or more scientists responsible for the data

- Has not been formally peer reviewed yet but receives informal feedback that is publicly posted on the server

- Hot tip: if you come up against a gated article, check for a preprint version. Just be sure to check whether the preprint is outdated or if it’s been updated since the gated article was published.

Textbook or nonfiction novel (technical)

- Longform text on a topic or field

- Usually written by one or more field-leading experts

- Extensively reviewed and edited by the publishing company

- Often re-issued each year to include current information

- Provides an extensive account of the current understanding in a scientific field, summarizing the seminal research that has led to that understanding

Magazine/online article (technical, general, or trade-oriented)

- Written piece, surveying a topic in science

- Longform white papers or feature articles provide in-depth analysis

- Short-form news clips and product briefs give a few key details

- Usually either written by that outlet’s editorial staff, submitted by a contributor

- Usually follow specific guidelines and undergo a review process by the editorial staff to ensure information is being represented in a non-biased and factual fashion

- Often not written by researchers or scientists responsible for the data

- Some articles may be sponsored by companies and can be more promotional

Videos, webinars, online lectures, infographics (technical, general, or trade-oriented)

- Visual/auditory pieces that cover a topic in science

- Usually developed by an expert in the field in collaboration with a media outlet

- Follows specific guidelines and undergoes a review process by the editorial staff to ensure information is being represented accurately

- May be sponsored by companies to be more promotional and/or focused on their technology

Press release announcement (general, technical, trade, or business-oriented)

- One-two pages, high-level piece that announces a notable step or success

- Written by an affiliate of the organization making the announcement

- Writing guidelines and review process are up to the discretion of the company

- Inherently promotional

Blog (general, trade, technical)

- Written piece surveying a topic in science

- Can be written by people of various backgrounds and skillsets

- Often most reflective of the author’s viewpoint

- Rules preventing bias and ensuring accuracy may be enforced depending on where a blog is published (personal blog vs company blog, for example)

Social Media (general)

- Ideas and opinions shared freely

- Posts made by authenticated accounts and field leaders carry more weight

- No real oversight for bias, accuracy, truth

- Great way to sniff out the most current conversations and contrasting opinions, just be sure to follow up with other reputable sources

Wikipedia (general, trade, technical, business)

- Encyclopedia entries on a range of topics

- Written by a range of contributors

- Articles are reviewed by the Wikipedia community, and all writers and sources are checked

- Can provide a stepping-off point to learn terminology and basic principles, and find useful sources

Factors that Affect Trustworthiness and Confidence

There’s no shortage of places to read up on scientific information, but the old adage “don’t believe everything you read” is as true as ever – even when you’re combing through highly credible peer reviewed material. As you’re researching a topic, use the following questions to help evaluate the trustworthiness of information you’re reading.

- What kind of outlet published this information?

- How was the piece reviewed, if at all?

- Who wrote this?

- What is their expertise?

- Do they have scientific training? What is their level of experience?

- Are they a journalist?

- Was this written by/sponsored by an institution (university, industry, non-profit, policy, governmental) that has a high level of expertise but also a vested interest in the topic?

- Was data collected?

- Are the methods clear and detailed?

- Is the information being conveyed in a clear, equitable way?

- Are there conflicts of interest (declared or otherwise)?

- Is the author/institution/outlet known for controversy?

- How long ago was it published?

- Does it have significant references? Do they agree or disagree with the information?

With these answered, you can work to determine your relative confidence in the information. In statistics, confidence intervals represent the likelihood that an outcome or result accurately reflects reality. To calculate them, researchers plug accuracy influencing factors, or variables, into an equation to evaluate the certainty of a conclusion. In a similar way, there’s a sliding scale of certainty when it comes to establishing confidence in a piece of information, albeit more qualitative than statistics. Below are certain factors that can either raise red flags or make information more trustworthy.

| Factors | Higher Confidence | Lower Confidence |

|---|---|---|

| References | Numbers and claims sourced from peer reviewed work | Numbers and claims stated without a source |

| Bias | Nonpromotional or moderately promotional | Clearly pushing a product or company |

| Logic | Logically sound, clearly laid out | Leaps in logic, poorly explained |

| Accuracy | Accurate according to other literature | Claims are overstated or conflict with the literature |

| Objectivity | Cites counterpoints and explains where they fit in the narrative | Does not mention salient counterpoints |

| Context | Describes the history and current standing of the field | Does not explain the background behind the topic being discussed |

Three Examples

1) Imagine we find an article about a new product singing that product’s praises. The article claims that the product helps 95% of people solve a problem, but never explains or cites where that number came from. In this case, we would immediately be less confident about the information in that article. On the other hand, if we’re reading another article about the same problem, and the article summarizes the field, touches on contrasting viewpoints, and heavily cites the claims it makes, then we would feel much more confident about that article’s information over the first.

2) If we found a press release announcing a company’s new glass test tube product that is going to revolutionize the way that scientists do their work, we might be suspicious about the statement that such a simple tool is revolutionary, particularly when many other reagents, types of equipment, and ingenuity play bigger roles in most instances of experimentation. If instead we found a press release announcing a new brand of test tubes that stated that they were one of the many reliable, affordable products that the company offers with concrete indications of its value, then we would conclude that the second press release is less biased and more believable.

3) On the news, if reporters state that a technology is known to be effective against bacteria, and therefore it should be explored for COVID-19, we would be immediately struck by the leap in logic. Bacteria and viruses are completely different organisms, and what kills one may have no effect on the other. On the other hand, if the news reporter discussed a new technology that’s known to be effective against bacteria and viruses (including other respiratory viruses), we would be more likely to think that the technology could be effective against COVID-19, since it’s a smaller logical leap.

Our Mindset and Methodology

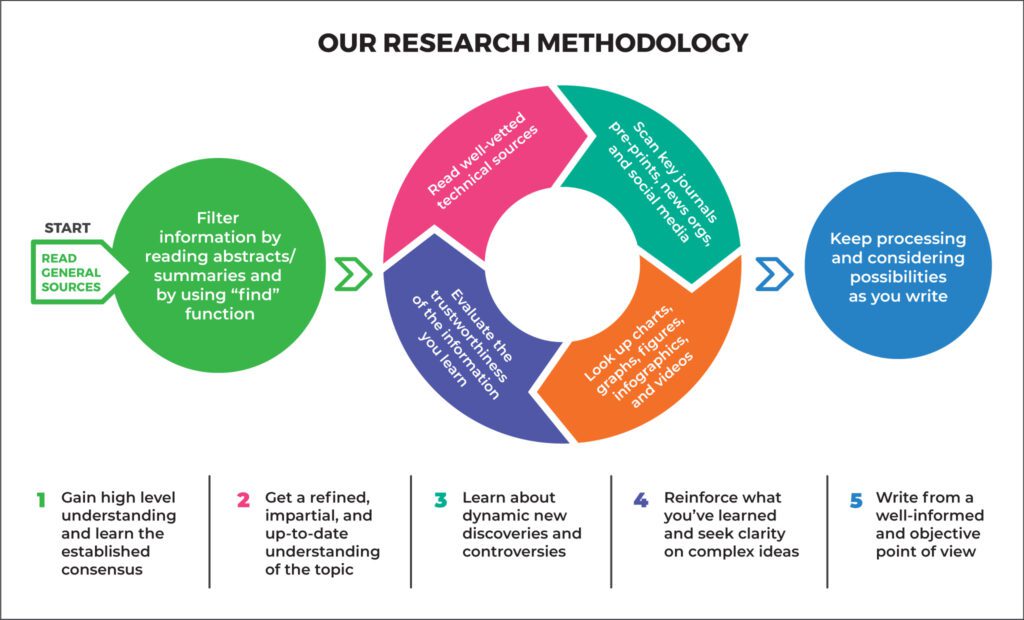

Reviewing a large number of sources and evaluating them can be daunting and time-consuming. Although time is pressing, hurrying can cost you down the line, so avoid skimming through a text until you are well-versed on the topic. As your knowledge grows, your pace will accelerate, especially if you apply a consistent methodology.

Start by learning the established consensus in the field by seeking out more generalized sources like Wikipedia, trusted blogs/authors, educational videos, and textbooks. These will give you a high-level understanding of concepts and define relevant terminology in friendlier language. Although the consensus in a field is not always correct, it is the firmest ground to lay a foundation, and it provides context for cutting edge or contentious ideas. Next, read well-vetted technical sources to drill down on nuance and ensure that you have an impartial and up-to-date understanding of the field. Specifically, we recommend academic review articles from high-impact journals. These peer-reviewed articles summarize the current standing of a scientific field and are subject to critique from many experts. Reading a review article published in the past couple of years will also give you important historical information, a laundry list of seminal research articles (and even other more specific reviews) published by leaders in the field to read, an overview of contrasting opinions, and active research questions.

At this point, it is likely you’ve encountered some concepts that are still not clear. No problem: Do a quick image search to find charts, graphs, figures, and infographics that explain things in a different way. A good figure can reinforce and clarify what you’re reading about, and it can lead you to an awesome new resource. Additionally, try searching for videos and animations that can bring a complex idea to life. If an idea still isn’t clicking, move on and keep researching – sometimes absorbing more information on a topic makes those difficult details come into focus all on their own.

Once you feel like you’ve got a good understanding of the topic, scan key journals, pre-prints, news orgs, and social media for fresh information. What have people been talking about lately? Are there new discoveries, controversies, or conflicts? You’ve read literature to learn the facts on the topic, but now it’s time to look at what people are talking about right now to understand the human factors at play.

Remember to be pragmatic and goal-oriented by defining what you need to learn to effectively do your job. Keep your audience in mind. Do they need a high-level overview, or will they be looking for specific details? What might they be most interested in learning? Not every source will provide information that’s useful to you, so remember to weed out irrelevant sources to avoid spending precious time reading them. Consider only reading a whole text if your specific question is explicitly referenced in the abstract or summary. Use the “find” function to search for relevant words and pull out the information you need without reading the entire document.

Throughout this process, be objective and flexible when forming thoughts and opinions. Give equal weight to all well-vetted sources. As you’re making your own outline or writing up your own deliverable, keep processing what you’ve learned as you’re writing about it. This practice often helps complex ideas solidify and triggers revelations. If you learn a fact that doesn’t fit with your current understanding of the topic, remain objective. Continue your research and always be open changing both your mind and narrative if you come across a good reason to do so.

Go Get ‘Em!

Read through scientific information with a critical eye, and sooner than you think, you will have developed an informed, complex, and up to date understanding of a new field – and with that you will be ready to share what you’ve learned with others!